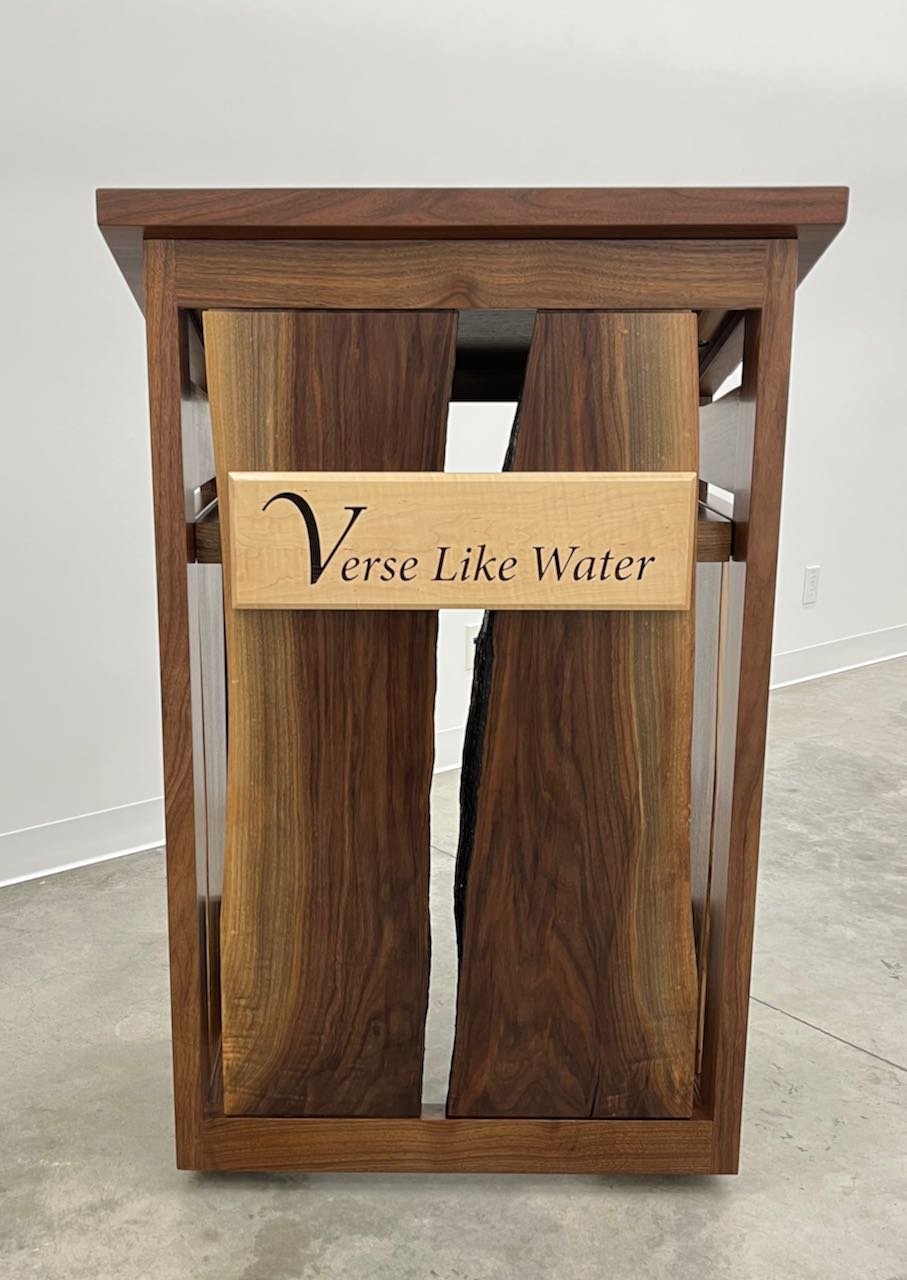

Podium with a Poetry Purpose

Ryan Kutter, Lead Woodworker

Last fall we were approached by Central Lakes College to develop a podium to replace what I remember English faculty member, Jeff Johnson, referring to as an “ancient warship of a thing.” This podium will serve Verse Like Water, a poetry series that brings national poet laureates and new voices to speak and engage with both college and high school students in central Minnesota.

The design parameters were broad but required the new podium to be about 30% smaller than their existing “warship” (some speakers were lost behind it), be easily moveable, and have a sign on the face that could be switched out between Verse Like Water events and commencement for the college. Last of all, they asked that it be constructed of live edge walnut slabs.

Such open-ended design guidelines from a client are a generous gift but can be intimidating. Once sketches start hitting paper the character of the piece can diverge into wildly different directions (not all of them good). There is safety in sticking with well-practiced forms, but perhaps also boredom in the design and effect. The requirement of live-edge walnut slabs meant that we were dependent on the unique grain curves of what we had in inventory or could find in our local world of sawmills, and that we were giving some control of design over to the shape of those pieces of wood.

In gathering materials we used large slabs that had been given to Abbey Woodworking many years ago by the artist Joseph O’Connell, as well as a tree that had been cut at Saint John’s within the past ten years, and a few more boards from a local sawmill. We are on the northern climate range of black walnut and it is a dear thing to use in our shop.

After several drafts of different possibilities we settled on a linear, straight-lined framework that would contain the natural edged pieces. Hoping to create a lighter sailing vessel, we suspended the curved boards within the framework to allow for a lighter visual effect. Only a few people will ever have to move it, but any audience will experience the sight of it as something that is either graceful or has a hulking presence.

The primary pieces on the face of the podium were natural edge (peeled bark) on one side, and a beautifully textured crack on the other that had healed into a pebbly, ebony like surface while the tree was standing alive. Matching the weathered surfaces to face each other maintained an open branch like effect, and can also be seen as a waterway coursing down, recalling the Mississippi that flows through central Minnesota and partially inspired the Verse Like Water metaphor.

Because walnut is such a dark wood we felt the need to use a bright maple plaque as contrast, with the two logos engraved black so they would be legible from the audience. The waving pattern of the curly maple has a watery shimmer that fits the metaphor of the program.

In the end we hoped to make a flagship piece for Central Lakes College and Verse Like Water, something that would enhance their events and be noteworthy enough not to become furniture clutter. On the other hand, the podium is only a vessel for the speaker of the moment and the audience that gathers, and it shouldn’t be a distraction or try to steal attention for itself.

These are often the tensions in a good piece of furniture, a dialogue between the voice of the wood, designer and craftsman, and between being a simple tool to serve and being a thing of beauty that serves well.

Winter has yet to release its grip on Central Minnesota, with more snow in the past day. Fortunately, the roof is keeping snow and rain out of the building and the walls are keeping the wind from blowing through. This has allowed for the concrete flooring to be poured and woodworking staff to tour the space. In the next weeks, work will continue on both the inside and outside of the building with painting, insulation, and brick work. We’ll keep you updated on the progress or check out our website for the live camera.

A Note on the Natural Edge and George Nakashima:

The use of natural edge wood, particularly with walnut, has become popular in the United States since it was developed extensively by the American woodworker George Nakashima (1905-1990). Anything with a “live edge” might be referred to as “Nakashima style.”

Many woodworkers fell in love with the craft because of George Nakashima and his spiritual and creative approach to his work, which emphasized integrating life with the natural world. Some of his work is easy to imitate because it depends largely on a beautiful piece of wood left to speak for itself, and in some imitations requires minimal woodworking skills (such as mounting a slab on a tube steel frame rather than wood).

This ease of imitation leaves some professional craftsmen skeptical of natural edge furniture as a fad that will pass, but I think the beauty of elevating a singular piece of wood is a great opportunity that Nakashima gave to our culture. Surely there is room for amateurs to do this as well as the more complicated versions done by Nakashima and now others.

Trained as an architect and a careful draftsman whose catalogue includes a wide range of pieces using standard dimensional lumber, Nakashima first began woodworking in an internment camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II. In the camp, Nakashima (the internationally trained architect) partnered with a carpenter who had learned traditional joinery in Japan. They used what they could find, scrap lumber and rough-edged wood, to make their incarcerated years more beautiful and tolerable.

When he established his woodshop in New Hope, PA, Nakashima was poor, and often made do with scraps from the sawmill down the road. This forced limitation of having to use firewood and his familiarity with a natural aesthetic from Japanese culture helped lead his creative path to the icon that he has become, and into a person whose singular vision can’t be imitated.

Nakashima’s daughter, Mira Nakashima, still operates George Nakashima Woodworkers, developing new furniture (she herself is a trained architect and designer) as well as maintaining production of George’s designs.

As a Roman Catholic who designed a number of church buildings and liturgical environments (including the chapel and original buildings at Christ in the Desert monastery in New Mexico), Nakashima would occasionally quote the Rule of Benedict during his artist talks. His commitment to community, work, and prayer through woodworking and design shares a foundational affinity with the ora et labora (work and prayer) of Saint John’s.